Best Time of Day for Induction: How Timing Affects Labor Length and Cesareans

The 6-Hour Difference: Why When You Start Your Induction Changes Everything

When we talk about induction, the conversation usually focuses on the medical necessity or the methods used. But new data suggests we’ve been ignoring a critical variable: The Clock.

A large-scale study of 3,363 term inductions at a U.S. hospital (2019 - 2022) suggests that the time of day an induction begins can be the difference between a smother, less complicated birth and an exhaustive, multi-day ordeal. (If you’re a doula or a mom who has had that experience, you know exactly what I’m talking about).

And when you layer in what we know about melatonin, hospital lighting, and your body’s internal clock, this becomes a powerful conversation to have with your provider.

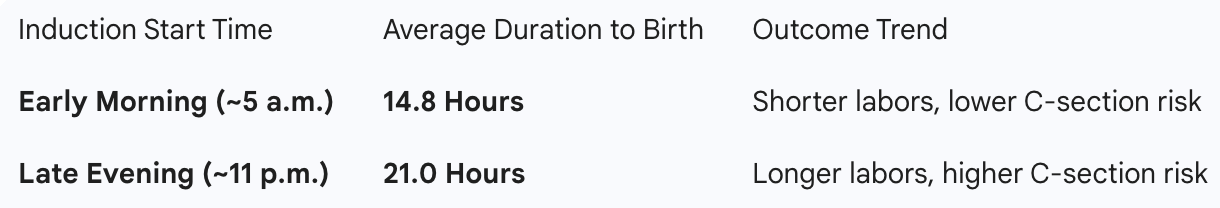

What is the average length of a morning induction?

The study followed women at 37+ weeks, carrying a single baby, with no prior C-sections. By grouping induction start times into three-hour windows, a clear pattern emerged:

Timing of induction of labor

That 6-hour difference isn't just a statistic; it represents six fewer hours of contractions, medical monitoring, and physical exhaustion. Crucially, the study noted that while maternal outcomes improved with morning starts, infant health remained excellent across all groups.

Who benefits most from an early morning induction?

The early‑morning advantage wasn’t equal for everyone. Two groups stood out:

· First‑time mothers.

o On average, their inductions lasted about 24.9 hours, compared to 14.4 hours for women who’d given birth before.

o For first‑time women, shorter inductions and lower cesarean rates were linked with finishing within that 12 - 24‑hour window, not going beyond 24 hours.

· Women with a higher BMI (obesity group).

o In this study, about 69% of women were in the obese BMI category. (I’ve written about ‘BMI labeling’). Dr Sara Wickham is a great resource in this area.

o For these women, the shortest inductions were when labor started between 6 - 9 a.m., and there was a clear daily rhythm in how long induction took across the 24‑hour day. (Yes this is right around handover.)

When they put body size and birth history together:

· First‑time moms with a normal BMI had a higher chance of delivering when induction started just after midnight (around 12–3 a.m.).

· First‑time women considered obese had a higher chance of a vaginal birth when induction started in the 6 - 9 a.m. window.

If this is your first baby, and especially if your BMI is higher, you may have the most to gain from an induction time that matches your body’s natural rhythms.

Deep Dive for Induction Timing for Moms with GD or Higher BMI

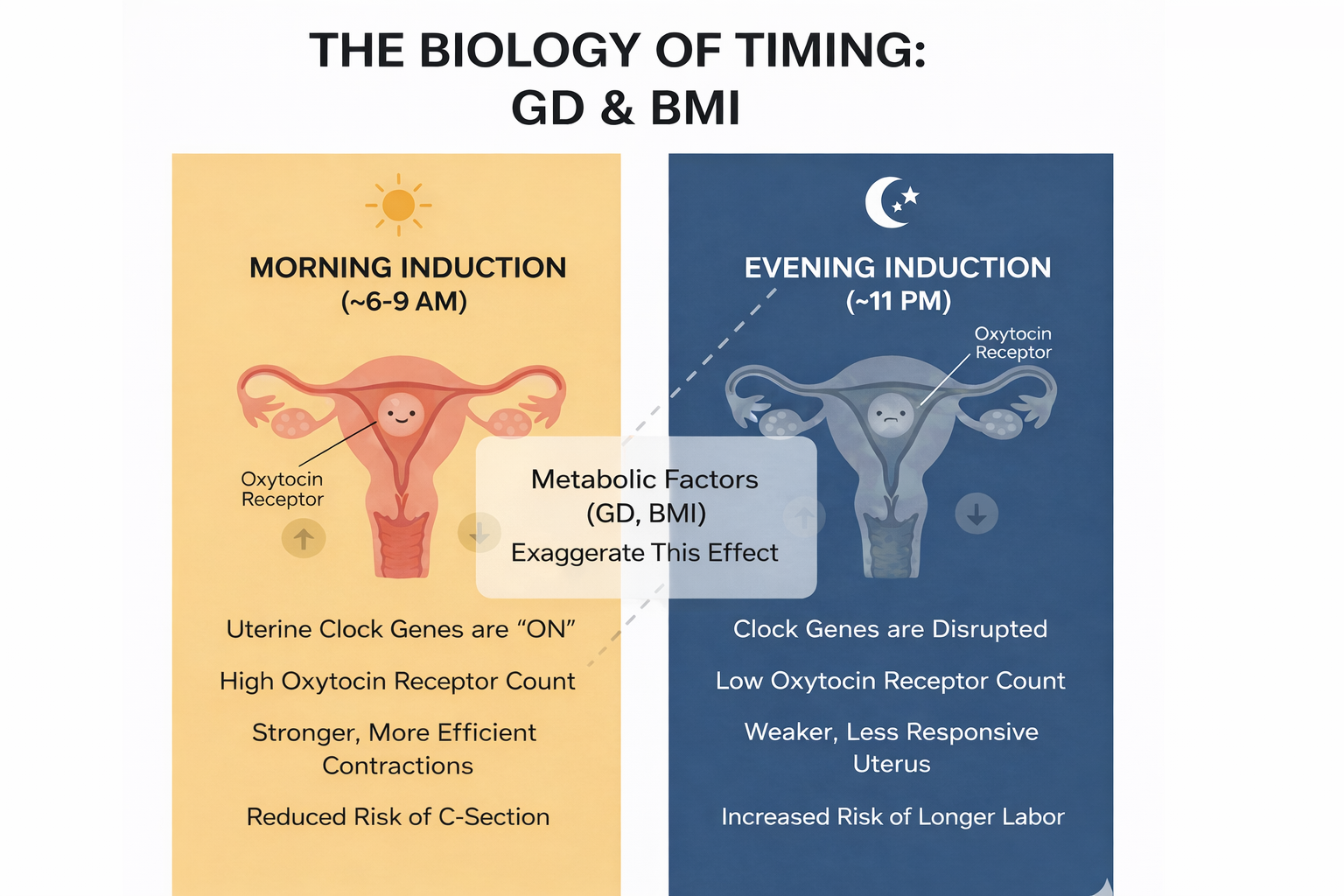

“The Science of the “Uterine Clock”: A Note for Gestational Diabetes and Higher BMI

For women managing gestational diabetes (GD) or those with a higher BMI, the timing of an induction isn’t just a matter of convenience - it’s a matter of cellular biology.

Research into the myometrium (the muscular wall of your uterus) has revealed that our uterine cells actually have their own internal “clocks.” These cells respond to oxytocin differently depending on the time of day. However, these “clock genes” can sometimes be disrupted by metabolic conditions like GD or obesity.

Why Timing is “Extra” Important Here:

The Oxytocin Connection: In lab studies, when these internal clock genes are out of sync, the uterus actually produces fewer oxytocin receptors. This makes the muscular wall less responsive to the very medication (Pitocin) used to jumpstart labor.

A Clearer Benefit: The recent study of over 3,000 births showed that women with obesity - who often face a higher risk of gestational diabetes - showed a particularly strong response to morning starts.

The Optimal Window: For this group, the data suggests a “sweet spot” for starting induction between 6:00 a.m. and 9:00 a.m. to achieve the most efficient labor.

Talk to your provider about this research.

”

It’s not just drugs and doses - your body’s clock is involved

This is where it gets really fascinating.

We’ve known for a while that:

· Spontaneous labors and births naturally cluster in the late night and early morning hours.

· The hormone oxytocin - which Pitocin mimics - has a daily rhythm; levels and tissue sensitivity aren’t the same at 2 a.m. as at 2 p.m.

· The uterus has its own internal clock, and clock disruption can change how it responds to oxytocin in both animal and human studies.

In this new study, time of day mainly affected early labor:

· From the start of induction to about 6 cm dilation.

· Not so much the active phase or pushing.

This suggests that early‑morning timing is especially helpful for cervical ripening and early contractions, where oxytocin and other signaling molecules (like prostaglandins) do a lot of the heavy lifting.

“In other words: It’s not just “how much Pitocin” you get. It’s when your uterus and cervix are most ready to listen.”

Hospital lighting: why bright light at night works against you

Now let’s talk about something most birth plans skip: light.

Your body makes melatonin mainly in the pineal gland in your brain. Pineal melatonin:

· Rises in the dark at night.

· Is very sensitive to light at the eyes, especially blue‑rich light from overhead LEDs and screens.

· Helps coordinate your whole circadian system: sleep, hormones, uterine activity, and even your baby’s developing clock.

Research in pregnant women shows:

· Hospital stays and low, irregular daytime light can flatten melatonin rhythms.

· Night‑time light exposure suppresses melatonin.

· Using “biodynamic” or circadian‑friendly lighting, or even simple blue‑blocking glasses in the evening, can help preserve melatonin patterns in pregnancy.

Why does lighting matter for labor?

· At night, higher melatonin levels seem to boost uterine contractions, especially in partnership with oxytocin.

· One line of research has even shown that pregnant women exposed to blue/green light at night had lower melatonin and fewer contractions than those exposed to red light.

Now picture the typical hospital admission at 10 p.m.:

· You walk into bright overhead lights in triage.

· You’re under monitors, screens, staff coming in and out.

· Your eyes are getting blasted with blue‑heavy light exactly when your pineal melatonin should be peaking.

That light can:

· Blunt melatonin production at night.

· Potentially reduce its helpful role in uterine contractility and birth timing.

· Contribute to the same kind of “circadian disruption” that’s been linked with longer labors and more interventions in other studies.

So if you’re admitted for a late‑evening induction, you may be stacking two challenges:

1. Your internal clock and uterus may be less responsive to induction timing in the late evening according to the new study.

2. The hospital lighting may be actively suppressing the night‑time melatonin that normally supports contractions.

Melatonin 2.0: pineal vs mitochondrial (and why early morning might be a sweet spot)

There’s another layer that’s just starting to make its way into clinical thinking: melatonin inside your cells, especially in the mitochondria. (Most birth professionals aren’t aware of this).

We now know that:

· Mitochondria - the tiny powerhouses in your cells - can make their own melatonin locally.

· This “mitochondrial melatonin” helps protect cells from oxidative stress, supports energy production, and keeps mitochondrial quality control running smoothly.

· It’s not as tightly tied to the light/dark cycle as pineal melatonin, although the two systems interact.

Here’s how that might matter around induction:

· During the night, pineal melatonin is high, supporting uterine contractions and helping synchronize the timing of birth.

· As dawn approaches, pineal melatonin naturally drops - your brain shifts toward wakefulness.

· But your body may still be leaning on mitochondrial melatonin inside muscle and uterine cells to manage the intense energy demand and oxidative stress of labor.

So when the new induction study finds that women do best (in terms of shorter inductions) with starts between roughly 3 - 9 a.m., you can imagine a window where:

· You’re coming out of the pineal melatonin peak into a more wakeful state (easier for staff, for you, for decision‑making).

· Your uterine tissues still carry the “afterglow” of night‑time circadian support and local melatonin signaling at the cellular level.

· Your mitochondria are working hard and may be better protected by this internal melatonin, especially under stress.

We’re early in understanding this, but the takeaway for parents is:

Your body has a built‑in rhythm for when it likes to labor, and both brain melatonin and cellular melatonin are part of that story.

A 6 hr difference could be the difference in exhaustion, birth trauma and an unplanned in labor cesarean.

How to talk to your OB about timing and light.

You don’t have to be a chronobiology nerd to have a respectful conversation. Here’s a simple framework and language you can use.

1. Ground it in the evidence

You might say:

“A 2026 study in American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM followed over 3,300 term inductions. They found that starting induction in the early morning - roughly 3 - 9 a.m. was linked with significantly shorter labors and fewer cesareans, without worse outcomes for babies. Late‑evening starts around 9 p.m. - midnight had the longest labors and higher caesarean rates.”

If this is your first baby or your BMI is higher, add:

“First‑time women and women with higher BMI benefitted the most from morning inductions in that study, and longer inductions over 24 hours were tied to higher caesarean rates.”

2. Ask directly about scheduling

Then ask:

“Given that data, is there any flexibility to schedule my induction in the early morning instead of late at night? Even starting around 5 - 9 a.m. seems to make a big difference in average labor length.”

You’re not demanding - just inviting your clinician to partner with you around timing.

3. Bring light into the conversation

You can also gently raise the lighting piece:

“We know that bright blue‑white light at night suppresses melatonin, and there are even studies in pregnant women showing that night‑time light exposure reduces melatonin and can change contraction patterns. Since melatonin normally works with oxytocin to support labor at night, I’d love to keep the room lighting as soft and warm as possible, especially if I’m here overnight.” (Most OBs don’t care if your room is lit up like Vegas so this may be new information for them and they likely won’t care how your room is lit other than for the birth itself or of course if you’re having an epidural).

Practical requests you can make:

· Dim the overhead lights whenever it’s safe.

· Use lights with less than 2% blue light in your birth room where possible.

· Limit constant screen glare in your line of sight.

· Consider blue‑blocking glasses in the evening (clear this with your care team first) as one trial showed these helped protect melatonin in pregnant women.

These are all low‑risk, common‑sense changes that align with the hospital’s goal: a smoother, safer labor.

Frequently Asked Questions About Induction Timing, Circadian Rhythms, and Hospital Lighting

1. Does the time of day I’m induced really matter?

Yes. A large 2026 study of 3,363 term inductions found that labor was shortest when induction started in the early morning and longest when it started late in the evening or at night. Early‑morning starts (around 5 a.m.) averaged about 14.8 hours from induction to birth, while late‑evening starts (around 11 p.m.) averaged about 21 hours.

2. Does induction timing affect my baby’s safety?

In this study, no. NICU admission rates and common newborn problems (breathing issues, low blood sugar, jaundice, feeding difficulties, suspected infections) were not significantly different across times of day. The big differences were in how long labor lasted and how often women needed a caesarean, not in baby outcomes.

3. Who benefits most from early‑morning induction?

Two groups saw the clearest benefit:

· First‑time mothers, who already tend to have longer inductions overall.

· Women with a higher BMI (obesity category), who showed a strong daily rhythm in induction length and did best when starting between about 6–9 a.m.

If you’re a first‑time mum and/or your BMI is higher, you have the most to gain from discussing early‑morning timing with your OB.

4. Is this just because of hospital staffing or shift changes?

The study authors adjusted for key factors like age, BMI, whether the woman had given birth before, and Bishop score (cervical readiness). They still found a strong time‑of‑day effect, especially in the early part of labor (from induction start to about 6 cm dilation). That suggests maternal biology and circadian rhythms, not just staffing patterns, play a major role.

5. What induction methods were used in the study?

The study included term inductions started with:

· Synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin)

· Cytotec (misoprostol) as a cervical ripening agent

· Foley catheter (mechanical ripening)

· Cytotec + Pitocin combinations

Time‑of‑day had a significant impact for women induced with Pitocin alone and Cytotec alone, but not as clearly for Foley catheter or combined protocols.

6. Were Bishop scores (cervical readiness) taken into account?

Yes. Bishop score was recorded and included in the statistical models. The time‑of‑day effects on induction length and caesarean risk were seen even after adjusting for Bishop score, which means they weren’t just due to some women starting with a more “favorable” cervix.

7. Why would my body respond differently to induction at different times?

Your body runs on a 24‑hour circadian clock. Hormones like oxytocin and melatonin follow daily rhythms, and the uterus itself has an internal clock. Research suggests that at certain times—especially in the late night and early morning—your uterus and cervix may be more responsive to oxytocin and better primed for contractions and cervical ripening.

8. How does hospital lighting affect labor and melatonin?

Bright, blue‑rich light (like typical overhead LEDs and screens) at night can suppress pineal melatonin, the hormone your brain releases in the dark. Melatonin normally rises at night and works with oxytocin to support uterine contractions and the natural timing of labor. When you’re admitted under harsh lights at night, that melatonin surge can be blunted, potentially working against your body’s natural labor rhythm.

9. What’s the difference between pineal melatonin and mitochondrial melatonin?

· Pineal melatonin is made in the brain at night and is very sensitive to light. It coordinates your overall circadian rhythm, sleep, and many hormonal signals.

· Mitochondrial melatonin is produced inside cells, especially in the mitochondria (your cellular “powerhouses”). It helps protect cells from stress and supports energy production and repair.

During labor, especially in the early morning when you’re waking up, pineal melatonin naturally drops, but local mitochondrial melatonin may help your muscles and uterus handle the heavy workload.

10. Can I do anything about hospital lighting during my induction?

You can’t redesign the building, but you can often:

· Ask staff to dim overhead lights when it’s safe.

· Use lamps or side lights instead of full bright lights.

· Limit screen glare near your face at night.

· Bring an eye mask or consider blue‑blocking glasses in the evening.

These small changes help protect your night‑time melatonin and support your body’s natural labor timing.

11. Does this mean evening inductions are “bad” and should always be avoided?

Not necessarily. Sometimes medical needs, staffing, and bed availability mean an evening start is the safest or only option. The key takeaway is:

· When you do have a choice, early‑morning induction appears to be more aligned with your body’s natural rhythms and may reduce the length of labor and your chance of an unplanned cesarean.

· Even with an evening admission, focusing on softer lighting, strong daytime light exposure before admission, and good sleep patterns can still support your circadian system.

12. How can doulas and birth workers use this information?

Doulas and midwives can:

Share this blog!

· Educate clients that induction timing and light are modifiable factors that may influence their birth experience.

· Encourage women to discuss early‑morning options when planning elective or semi‑elective inductions.

· Advocate for more circadian‑friendly lighting in labor wards and help create a calmer, dimmer environment at night when appropriate.

Study Limitations

This study is exciting, but it isn’t perfect. It looked back at births from just one hospital, so the results might not be the same everywhere. Women weren’t randomly assigned to morning or evening inductions, and the authors didn’t fully separate why each woman was induced, so some hidden factors could influence the patterns they saw. The group of women with a normal BMI was quite small (around 5%), and they couldn’t dig deeply into every induction method or dose. Finally, they used time‑of‑day as a stand‑in for body clocks without directly measuring things like melatonin or light exposure, so the biological explanation, while very plausible, is still indirect.

Resources:

https://blog.tracydonegan.org/blog/the-hidden-dangers-of-blue-light-exposure-during-pregnancy

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6753220/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9291618/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22324558/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9774480/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8728098/

https://grantome.com/grant/NIH/R21-HD086392-01

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10215173/

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1705768114

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1332567/full

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11107735/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-021-01464-x

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1567724919302569

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jpi.12360

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2024ESPR...31.3425L/abstract